First, a big announcement—then we will dive into Supreme Court matters, 1947.

On May 7, 1947, Sid Olson received a letter from General Courtney H. Hodges, Headquarters First Army, Office of the Commanding General, Governors Island. It read: “We of the Army are grateful to you for your part in the magnificent accomplishment of reporting throughout the war. Your day-by-day account of events as they occurred will be the basis of the history books of tomorrow.”

But Olson was too busy to dwell much on the war. He was excited about heading to D.C. for six weeks, mid-May through June, to launch a brand-new LIFE column called “Capital Letter.” According to his diary, he had booked a room at the Mayflower Hotel.

For his first piece, he wanted to discuss Supreme Court Hearing 331.US367, Craig vs. Harney, May 28, 1947. During the war, Olson had become more concerned about the freedom of the press and censorship. The document he wrote—included in its entirety below—provides an incisive view into the post-war concerns of the Supreme Court. It is amusing, snarky, astute, sexist, historically relevant, and though I’m no lawyer, it probably speaks to the concerns of our own press in 2025 (I am a huuuuge fan of

. For more info on this particular case: Justia U.S. Supreme Court.His column was never published, to my knowledge, so you can say you saw it here FIRST! And you will not find this column in my book “Following the Front”—it did not make the “cut.” You’re welcome! The original now resides at the Beinecke Library, along with the rest of Olson’s papers. I hope you will buy a copy of my book; links to online venues are located at the foot of this page.

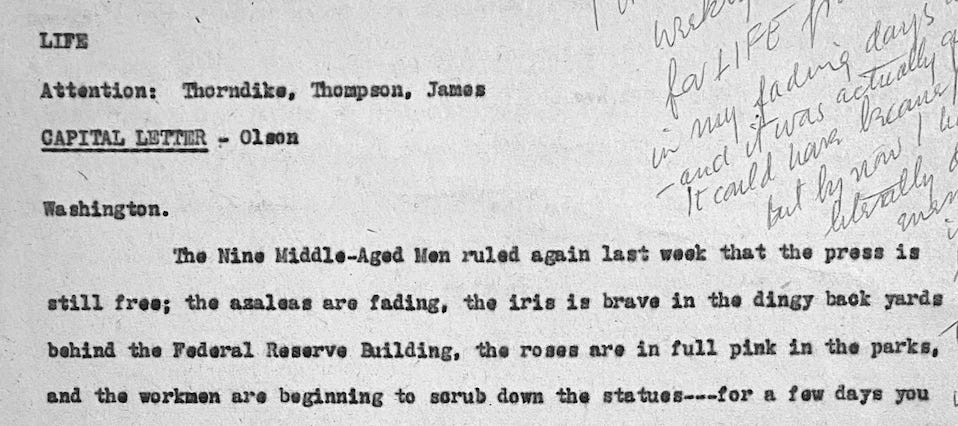

LIFE

Attention: Thorndike, Thompson, James

CAPITAL LETTER - Olson

Washington.

The Nine Middle-Aged Men ruled again last week that the press is still free; the azaleas are fading, the iris is brave in the dingy back yards behind the Federal Reserve Building, the roses are in full pink in the parks, and the workmen are beginning to scrub down the statues—for a few days you will be able to see Farragut, von Steuben, and Pulaski plain, before the pigeons roost again. The D.A.R., in all its stiff-girdled majesty, has taken over the town, arousing the usual suffocating awe in the unlucky male cub reporters trapped among the massive bosoms. Like medium tanks, upholstered in chintz slip-covers for the summer, the great ladies float through the Mayflower lobby, liberally using the word "cute" to describe each other; grinding down the morale of room-service waiters with nickel tips for the service of twelve teas, and bringing despair to Serious Thinkers with this year's gift of $100,000—not for cancer research, not for veteran rehabilitation, not even for fellowships for water-colorists---but for a bell-tower. The U.S., of course, needs a bell-tower like a hole in the head.

Only two reporters were present at the usual Monday spectacle of the Supreme Court Justices quarrelling in public; the regular Court press-corps, blasé and impatient, lolled as usual on the leather couches in the quartered-oak-panelled press-room downstairs---and thus missed an hour of purest entertainment at the highest level: the Intellectual chess-game played in public by the Justices on each Decision Monday. The subject was the freedom of the press, guaranteed unequivocally in the First Amendment to the Constitution, but often needing reaffirmation, which this time came by vote of 6 to 3.

The case was that of a publisher, an editorial writer and a reporter of newspapers published in Corpus Christi, Texas (pop. 60,000). In August 1945 a layman judge in the County Court had balked three conservative verdicts by a jury, which then ruled according to his instructions, but under protest. The plaintiff then asked for a new trial. The same judge denied the motion, and then, smarting under heavy blasting in the local papers, sentenced the three newspapermen to jail for contempt of court. The Court of Criminal Appeals in Texas ruled against the newspapermen's appeal, and the case reached the Supreme Court this term.

The majority of six Justices reversed the Texas ruling. The decision, written by Justice William O. Douglas, was read in his absence by Justice Stanley Reed---Justice Reed now reading quite calmly and dryly from the Bench before which once his voice shook and then failed, as he fainted dead away back in 1936 as he made his first arguments, as the then U.S. Solicitor General, before the frosty gazes of the Nine Old Men. The Douglas decision held, in sum, that freedom of speech and the press must not be impaired through the use of judicial power “unless there is no doubt that the utterances in question are a serious and imminent threat to the administration of justice.”

The decision reflected the attitude of a majority of the Justices to the constant criticism of the present Supreme Court. Granting that the newspaper reports in question were unfair, inaccurate, and sketchy, Mr. Douglas did not find these “any imminent or serious threat to a judge of reasonable fortitude” and went on: “The law of contempt is not made for the protection of judges who may be sensitive to the winds of public opinion. Judges are supposed to be men of fortitude, able to thrive in a hardy climate.”

Justice Frank Murphy, concurring separately to demonstrate his own fortitude against the powerful currents of gossip that have swirled about his balding red head for years, nobly turned his other cheek to Westbrook Pegler: “Unscrupulous and vindictive criticism of the judiciary is regrettable. But judges must not retaliate.....Silence and a steady devotion to duty are the best answers to irresponsible criticism….”

But Justice Robert H. Jackson would have none of this masochistic humility. He took off like a fleet of bombers to crunch his brethren; his separate dissent, much stronger in his ad lib than in his printed remarks, was a long roar of defense of the right of judges to judge without botheration by the press. “I do not know whether it is the view of the Court that a judge must be thick-skinned or just thick-headed, but nothing in my experience confirms the idea that he is insensitive to publicity……From our sheltered position, fortified by life tenure...it is easy to say that this local judge should have shown more fortitude.”

This opinion, delivered forcefully, brought buzzes from the 250 citizens who crammed the little temple, centered deep in the $9,000,000 worth of white marble that houses the Nine Middle-Aged Men. But now Chief Justice Vinson left off nodding and grinning genially at his acquaintances in the room to give the go-signal to Justice Felix Frankfurter, who immediately stole the show with one of his most brilliant classroom performances. Delivering, without notes, the dissent in which he was joined by the Chief Justice, Mr. Frankfurter appeared like a man in a cold but controlled rage. Two things seemed especially to irk him: The quotation by the majority of Mr. Justice Holmes on their side of the case, and their assumption that judges should be men of fortitude. By dividing and subdividing the issues with his superb legal skill he finally, in effect, got the question at issue down to what was Mr. Justice Holmes’ attitude toward the press? He made it very clear that Mr. Holmes and his attitudes toward any subject are his own special pigeons, and that if the other Justices want to quote anyone they had better look elsewhere, for he will do all the definitive Holmes-quoting that is to be done. Said the man who owns Holmes: “Mr. Justice Holmes was an Olympian! He did not even read the newspapers--I repeat, he did not even read them! Why, one did not discuss current matters with Justice Holmes! He was an Olympian, far above these things.”

There seemed to be envy in his voice; one had the feeling that Mr. Justice Frankfurter, try as he might to live like Justice Holmes, is unable to resist the temptation to take a quick look at Dick Tracy each morning. Justice Frankfurter made clear his own belief that Justice Holmes never intended to tolerate press campaigns against the judiciary, and he said, referring to the quotation of Holmes by the majority: “I can only remotely imagine the phosphorescent words that would come to his mouth if he heard himself quoted in this connection.”

And, as usual, the citizenry can only remotely imagine the phosphorescent words exchanged by the Justices in their conference room at the Saturday morning sessions over this “narrow, but far-reaching” Corpus Christi decision.

—SIDNEY OL SON

BUY THE BOOK!

What spectacular writing and a fascinating piece of journalistic sociology! Your introduction correctly names the combination of snark, misogyny, and eerie relevance.

Extraordinary language!! And to think that not a single republican President since Nixon could or can even complete a coherent sentence. There’s something important missing and it’s not just the words.